|

The 1992 Rio de Janeiro declaration embodied international recognition that global warming and climate change, driven by anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, pose a significant risk to the world’s economy, environment, and security and demand a cooperative effort between nations. It is often forgotten in today’s debate in the United States that the Senate ratified this agreement and thereby committed our country to address this challenge. Nearly a quarter century later, at the historic Paris Conference of the Parties in late 2015, numbers were attached to the broad Rio declaration: Nations, both developed and developing alike, put forward specific goals for GHG emission reductions in the 2025–2030 timeframe. These national goals reflect the enormous scientific understanding developed in recent decades. With widespread compliance, they represent a reasonable path toward meeting an overarching goal: limiting global warming to two degrees Celsius, or possibly less. The two-degree goal would call for meeting much more ambitious GHG emission reduction goals beyond 2030. Presumably the industrialized countries, with large per capita GHG emissions, would be called on to make especially significant early reductions of their energy sector emissions.

|

In fact, progress has been made. In the United States, both market forces (through the substitution of natural gas—and increasingly renewables—for coal) and federal and state clean energy requirements have substantially reduced carbon dioxide emissions. China has leveled its coal use. Many other countries have introduced and implemented policies to reduce emissions, including by the imposition of carbon emission charges, although much more needs to be done across the board. Furthermore, the June 2017 announcement by President Trump that he will pull the United States out of the Paris agreement sowed confusion as to where the world’s second-largest emitter (after China) was headed. Fortunately, state governors, city mayors, and business leaders soon made clear that they fully anticipated continued progress toward a low-carbon future and would stay the course or even accelerate their plans. We are not going back.

|

The issue is how we get there and how fast. Because of the cumulative nature of carbon dioxide emissions, time is of the essence. A failure to act decisively now exacerbates the challenge in the decades ahead. Success will require synergistic and innovation in technology, business models, policies, and regulations.

|

The scale of the greenhouse accelerator, once released, is almost unfathomable, and once it starts, it cannot be controlled. |

Hal Harvey and his coauthors have performed an important service in Designing Climate Solutions: A Policy Guide for Low-Carbon Energy. In this work, the focus is placed on how to reach these emission targets and which policies have a reasonable chance of getting us there. They have relied on decades of experience combined with quantitative analysis to present a portfolio of policy solutions for key climate change risk mitigation opportunities that have been shown to work in a variety of contexts and countries. The chapters thus serve as a handbook for policymakers on both national and subnational levels. Designing Climate Solutions addresses policies that provide economic signals, performance standards, and R&D support. Clearly, this suite of policy models needs adaptation to local, regional, and national circumstances, just as there is no single low-emission technology solution for different localities and countries. This book provides a valuable toolkit for policymakers committed to timely mitigation of climate change risks.

|

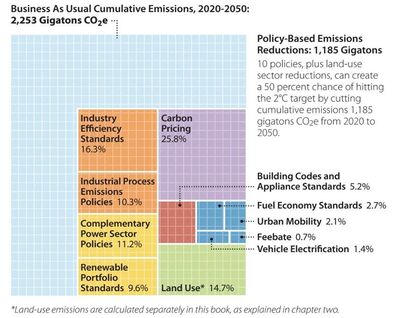

Harvey and colleagues promote pragmatic optimism for reaching the challenging two degree Celsius goal. In their approach, they embody the philosophy of Bostonian Willie Sutton, who is said to have answered the question of why he robbed banks with the response, “Because that’s where the money is.” Harvey and his coauthors emphasize that only 7 countries are responsible for more than half of the GHG emissions, and only 20 for three-quarters. So “that’s where the carbon is.” Thus, a small portfolio of proven policies, applied in a small number of countries, can yield enormous progress toward the global challenge of limiting global warming and climate change. The imperative is to move expeditiously, and this book provides an excellent foundation for effective policy design in diverse circumstances.

|

- Ernest J. Moniz, 13th U.S. Secretary of Energy

From Designing Climate Solutions by Hal Harvey, Robbie Orvis, and Jeffrey Rissman.

Copyright © 2018 Island Press. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, DC.

Copyright © 2018 Island Press. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, DC.