A city is experiencing an increasing number of seemingly random incidents. A major financial institution suffers system failures, sending shockwaves through the markets. Workers struggle to keep the public transportation system operating as critical control systems fail. Social media reports of terrorist attacks incite panic. The city’s first response capability begins to strain. Regional medical facilities are at capacity. The media struggles to inform an increasingly concerned public. Elected leaders and emergency response leadership gather in the city’s emergency operations center to analyze the situation and respond.

A sinister reality emerges when a foreign terrorist group claims that the city is under siege from cyberspace.

Although digital connectivity has made our infrastructure more efficient, it has made it more vulnerable to attack. As a result, infrastructure resilience is more critical today than ever before. Cyber attacks rarely affect a single target, instead their effects, anticipated and unanticipated, ripple across interconnected infrastructure sectors. Differing abilities to recognize a cyberspace attack, limited information sharing, varying defense capabilities, and competing authorities complicate the response. These gaps in cybersecurity leave our Nation vulnerable to exploitation by a determined adversary.

A sinister reality emerges when a foreign terrorist group claims that the city is under siege from cyberspace.

Although digital connectivity has made our infrastructure more efficient, it has made it more vulnerable to attack. As a result, infrastructure resilience is more critical today than ever before. Cyber attacks rarely affect a single target, instead their effects, anticipated and unanticipated, ripple across interconnected infrastructure sectors. Differing abilities to recognize a cyberspace attack, limited information sharing, varying defense capabilities, and competing authorities complicate the response. These gaps in cybersecurity leave our Nation vulnerable to exploitation by a determined adversary.

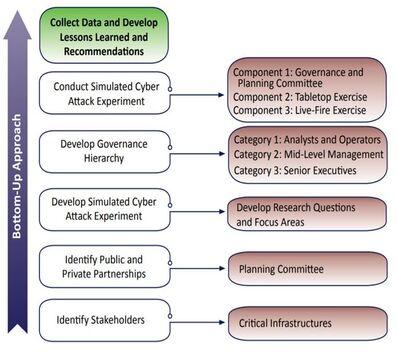

The Jack Voltaic Cyber Research Project is an innovative, bottom-up approach to developing critical infrastructure resilience. Developed by the Army Cyber Institute at West Point, the program was launched in order to conduct real-life, real-time and real-analysis of cybersecurity and protection gaps. The first iteration, Jack Voltaic 1.0, took place in New York in 2016. The second iteration, Jack Voltaic 2.0, was hosted by the city of Houston, TX in 2018. The Army Cyber Institute then launched programs in multiple port cities on the East and West Coasts of the U.S., and the findings from all of these workshops will inform a larger and much more ambitious Jack Voltaic 3.0 activity in 2020.

|

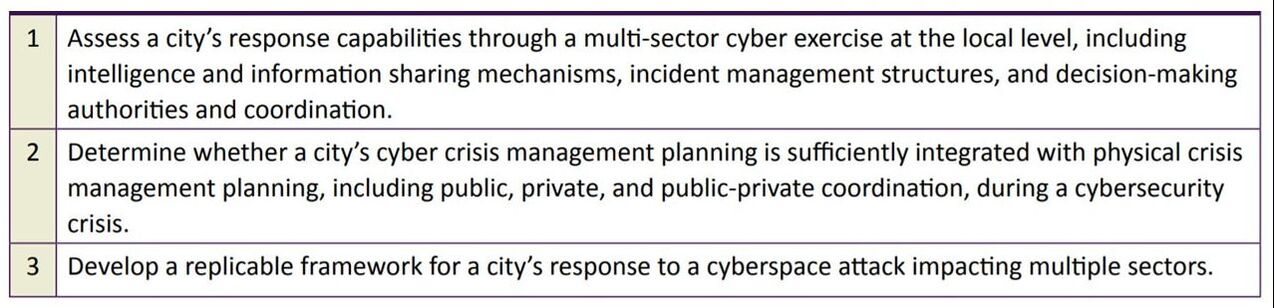

Scope and Research Objectives: JV 2.0 was an exercise event that demonstrated a physical attack and a cyber attack originating in Harris County, Texas, which impacted multiple critical infrastructure sectors in and around Harris County and the City of Houston, Texas. The experiment employed a cyber exercise involving players from eight critical infrastructure sectors. Through analysis of their perceived strengths and weaknesses, participants tailored the exercise to stress specific aspects of their incident response and disaster recovery plans. Its execution was the culmination of 13 months of planning, and involved 44 organizations and 200 participants from eight different critical infrastructure sectors.

|

Findings and Recommendations

Finding #1: Growing physical and cyber risk to cities requires a different framework for risk mitigation, due to current frameworks being inadequate to meet the changing and growing threat to urban communities. For the Nation to defend itself, US cities need an adaptable and scalable model to improve the cybersecurity posture. A bottom-up approach is required to integrate a risk-management framework that is replicable and adaptive to the rapidly evolving threat to urban communities.

Cyber attacks can quickly overwhelm unprepared governments, in light of their limited resources. According to a 2016 cyber security survey, only 33% of local governments had a formal, written cyber incident response plan. In February and March 2018, ransomware attacks seriously impacted online services in Atlanta, 911 dispatch services in Baltimore, and government networks in Davidson County, NC. This demonstrated the need for increased preparedness.

Recommendations:

Finding #1: Growing physical and cyber risk to cities requires a different framework for risk mitigation, due to current frameworks being inadequate to meet the changing and growing threat to urban communities. For the Nation to defend itself, US cities need an adaptable and scalable model to improve the cybersecurity posture. A bottom-up approach is required to integrate a risk-management framework that is replicable and adaptive to the rapidly evolving threat to urban communities.

Cyber attacks can quickly overwhelm unprepared governments, in light of their limited resources. According to a 2016 cyber security survey, only 33% of local governments had a formal, written cyber incident response plan. In February and March 2018, ransomware attacks seriously impacted online services in Atlanta, 911 dispatch services in Baltimore, and government networks in Davidson County, NC. This demonstrated the need for increased preparedness.

Recommendations:

- The JV approach can serve as a learning system and development effort. Undertake a series of JV exercises and hold educational workshops and conferences in key cities and localities to identify vulnerabilities, develop solutions, propose actions, and share best practices.

- The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), DHS, DoD, and the Department of Energy (DOE) should work together to develop a campaign to integrate the JV risk-incident response model into the exercise framework at the national level (i.e., collaboratively between DHS, DoD, and DOE). Ensure that military reserve component forces are incorporated as part of this effort.

- Develop technology offerings that enable the scaling of the JV 2.0 LFX component, in support of the National Defense Authorization Act Section 1649 - Pilot Program on Modeling and Simulation in Support of Military Homeland Defense Operations in Connection with Cyber Attacks on Critical Infrastructure.

- States, cities, and localities should seek research and development support from the Executive Branch and Congress to develop appropriate systemic approaches to cybersecurity.

- City and local cybersecurity efforts should better integrate the private sector, particularly critical infrastructure (e.g., electric grid, telecoms, water, and transportation). Public-private partnerships should evolve (i.e., move beyond service-level agreements) to induce a cultural change for building trusted relationships and working together.

Finding #2: The U.S. military and its allies are dependent on civil and commercial infrastructure. US infrastructure requires greater protection due to its vulnerability to sophisticated physical and cyberspace attacks.

While military installations have their own internal critical infrastructure providers, they still rely on service delivery from outside the installations’ boundaries. For example, electrical service is delivered through commercial providers to the installation, where it is distributed by the internal utility company. In the event the commercial provider cannot supply electricity, an installation can only run on backup power for a finite period and generally does so at a diminished capacity

Recommendations:

While military installations have their own internal critical infrastructure providers, they still rely on service delivery from outside the installations’ boundaries. For example, electrical service is delivered through commercial providers to the installation, where it is distributed by the internal utility company. In the event the commercial provider cannot supply electricity, an installation can only run on backup power for a finite period and generally does so at a diminished capacity

Recommendations:

- Improve Transportation and Maritime Sector Cybersecurity by collaborating with the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), and related Combatant Commands to develop an operational risk-management framework that better enables the protection of critical force protection elements. Ensure collaboration and planning include the Military Reserve, the National Guard, DHS, and DOE.

- Work with allies to develop similar integrated protection frameworks in transload areas abroad, and with frontline states. As a starting place, develop these efforts within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) through the development of support networks.

Jack Voltaic Research Objectives

Finding #3: National Guard units are providing physical security to support cities and are developing cyber capability. State military departments are currently working to evolve cyber‐response processes (including partnership strategies) and capabilities more rapidly.

For example, the Major General Tim Lowenberg National Guard Cyber Defenders Act has been proposed to create National Guard Civil Support Teams that serve at the discretion of state governors . If passed, it may provide a mechanism and funding to assist local authorities in establishing these teams, to bridge federal and non-federal response efforts during cyber incidents.

Recommendations:

Finding #4: States play a critical role in supporting city responses to physical and cyber events. States must develop campaign plans for more scalable incident responses and rapid information sharing. Several states are in the process of establishing fusion centers and Information Sharing and Analysis Organizations (ISAOs).

As an example, the State of Connecticut issued the Connecticut Cybersecurity Strategy in 2017 and the Cybersecurity Action Plan in 2018. The plan includes sections for state government, municipal governments, business, higher education, and law enforcement to address the following goals: cyber literacy, preparation, response, recovery, communications, and verification. In addition, other states (e.g. California, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Texas, Virginia and Washington) have also emerged as leaders within the cybersecurity realm, setting examples for other states to follow.

Recommendations:

For example, the Major General Tim Lowenberg National Guard Cyber Defenders Act has been proposed to create National Guard Civil Support Teams that serve at the discretion of state governors . If passed, it may provide a mechanism and funding to assist local authorities in establishing these teams, to bridge federal and non-federal response efforts during cyber incidents.

Recommendations:

- As cyber response procedural handbooks are developed, they should be shared across state military departments. Train the National Guard on procedures and assess the effectiveness of U.S. Northern Command, U.S. Cyber Command, and FEMA exercise programs.

- The DoD should maintain an inventory of existing and emerging critical Guard and Reserve cyber capabilities, which could be leveraged by state military departments, enabling better coordination between DoD and DHS. These capabilities should be tracked as they are developed.

Finding #4: States play a critical role in supporting city responses to physical and cyber events. States must develop campaign plans for more scalable incident responses and rapid information sharing. Several states are in the process of establishing fusion centers and Information Sharing and Analysis Organizations (ISAOs).

As an example, the State of Connecticut issued the Connecticut Cybersecurity Strategy in 2017 and the Cybersecurity Action Plan in 2018. The plan includes sections for state government, municipal governments, business, higher education, and law enforcement to address the following goals: cyber literacy, preparation, response, recovery, communications, and verification. In addition, other states (e.g. California, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Texas, Virginia and Washington) have also emerged as leaders within the cybersecurity realm, setting examples for other states to follow.

Recommendations:

- Develop, fund, and implement state‐wide incident response campaigns that leverage the JV 2.0 model. Working with other state agencies and community leaders, state emergency response coordinators should lead this effort and serve as the central resource for cities and localities in requesting assistance from state and federal governments.

- The DHS and associated sector-specific agencies should ensure DHS maintains accountability of these new assets (ISAOs) as they develop to evolve information sharing and ensure state and local homeland protection. Moreover, DoD should have the ability to leverage this capability to evolve campaign plans to defend the Nation.

- Leverage best practices and lessons learned from the financial sector’s Financial Systemic Analysis & Resilience Center (FSARC) to implement a similar model at the local and state levels Integrate overtime municipalities into the Intelligence Community process.

Over the last year almost all utility Chief Information Officers and

Chief Security Officers surveyed felt that cybersecurity threats have increased.

There is also decreasing confidence that the systems they have in place to control cyber threats can do the job.

Chief Security Officers surveyed felt that cybersecurity threats have increased.

There is also decreasing confidence that the systems they have in place to control cyber threats can do the job.

Finding #5: Policy and legal authorities at the federal and state levels do not sufficiently empower cities to respond to cyber incidents. Policies and authorities need to be reviewed and adjusted to better help cities defend against sophisticated physical and cyber threats. Currently, the exploration of cyber mutual assistance is only practiced within the energy sector.

In the course of the legal and policy TTX, key issues and shortfalls in current Defense Support to Civil Authorities surfaced. Additionally, the panel found policies were inadequate (e.g., cyber mutual assistance through National Guard and industry sectors across state lines). Additional progress is needed for continuously assessing comprehensive physical and cyber risk to cities and military installations.

Recommendations:

Finding #6: The private sector is affected by sophisticated adversarial cyber threats. The private sector can inform, develop, and provide solutions that benefit the public sector.

The private sector is frequently targeted by adversaries looking to profit from breaches. These attacks can result in a significant loss of business intelligence and intellectual property; therefore, establishment of a public-private partnership and increased regulation is essential. In addition, profit is not the only motive, as evidenced by the misinformation campaign during the 2016 U.S. presidential election and the Sony Pictures cyberspace attack. The private sector has incentives to cooperate with public and other private sector companies in the name of increased security.

Recommendations:

AES is pleased to provide Premium Members access to a true and correct copy of the full report.

Published with permission from the Army Cyber Institute at West Point.

In the course of the legal and policy TTX, key issues and shortfalls in current Defense Support to Civil Authorities surfaced. Additionally, the panel found policies were inadequate (e.g., cyber mutual assistance through National Guard and industry sectors across state lines). Additional progress is needed for continuously assessing comprehensive physical and cyber risk to cities and military installations.

Recommendations:

- Joint military organizations (e.g., National Guard Bureau) should explore possibilities in cyber mutual assistance practice. This would involve developing policy and associated implementation guidance that would lead to enabling a more proactive and sustained national military support to cities and localities defending against physical and cyberspace attacks.

- Support appropriate policy and implementation guidance development for local communities and state and national organizations. Annually develop and update national intelligence assessment of the cyber capabilities of nation-state and terrorist adversaries who exploit predictable natural and threat-based human generated events. The newly created DHS National Risk Management Center and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) should also be engaged.

Finding #6: The private sector is affected by sophisticated adversarial cyber threats. The private sector can inform, develop, and provide solutions that benefit the public sector.

The private sector is frequently targeted by adversaries looking to profit from breaches. These attacks can result in a significant loss of business intelligence and intellectual property; therefore, establishment of a public-private partnership and increased regulation is essential. In addition, profit is not the only motive, as evidenced by the misinformation campaign during the 2016 U.S. presidential election and the Sony Pictures cyberspace attack. The private sector has incentives to cooperate with public and other private sector companies in the name of increased security.

Recommendations:

- Key private sector representatives across multiple infrastructure sectors should gather (often) in a single group to learn about and receive the same answers to understand the appropriate context.

- Further explore the idea to create private sector “certified defenders” who have significant cyber security capabilities and who would work under government authorization to help prepare for and respond to adversarial cyber threats.

AES is pleased to provide Premium Members access to a true and correct copy of the full report.

Published with permission from the Army Cyber Institute at West Point.