Introduction

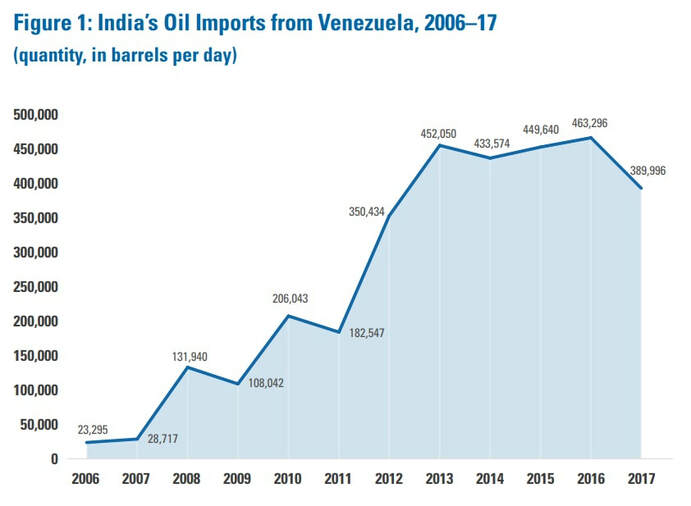

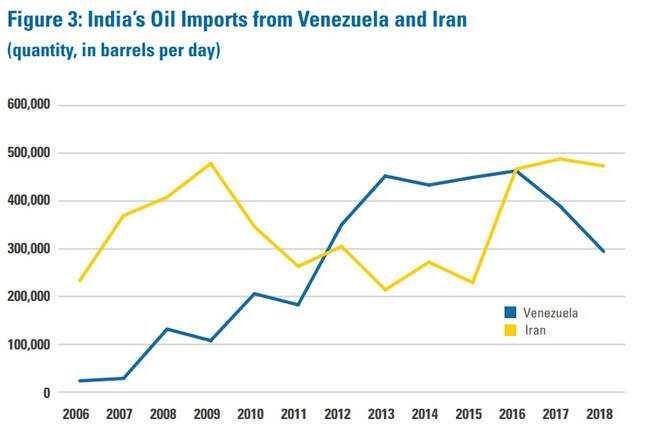

The year is 2007. Iran is India’s second-largest source of oil imports, totaling 367,000 barrels per day (bpd). The country is a stone’s throw from India, so close that both territories shared a land border before India’s independence from the British. India’s imports from Venezuela are a paltry 28,000 bpd in comparison, not surprising since Caracas is about 10,000 miles from New Delhi.

Cut to 2013. India’s oil imports from Venezuela skyrocket to 441,000 bpd, accounting for 12 percent of the country’s total oil imports. Meanwhile, imports from Iran plummet to 200,000 bpd by year-end. Suddenly, Venezuela doesn’t seem so far away. In February 2019, India is poised to become Venezuela’s largest cash market for oil exports, despite recently announced US sanctions. What caused this rather sudden and unexpected reversal of roles?

The year is 2007. Iran is India’s second-largest source of oil imports, totaling 367,000 barrels per day (bpd). The country is a stone’s throw from India, so close that both territories shared a land border before India’s independence from the British. India’s imports from Venezuela are a paltry 28,000 bpd in comparison, not surprising since Caracas is about 10,000 miles from New Delhi.

Cut to 2013. India’s oil imports from Venezuela skyrocket to 441,000 bpd, accounting for 12 percent of the country’s total oil imports. Meanwhile, imports from Iran plummet to 200,000 bpd by year-end. Suddenly, Venezuela doesn’t seem so far away. In February 2019, India is poised to become Venezuela’s largest cash market for oil exports, despite recently announced US sanctions. What caused this rather sudden and unexpected reversal of roles?

Three major factors, pertaining to India, Venezuela, and the United States, coalesced to bring Venezuela closer to India’s economic orbit.

First and foremost are India’s rapid economic growth and increasing thirst for oil. The first decade of the 21st century saw India’s GDP growing at 7.5 percent on average. This was accompanied by a rising demand for oil, used as transport, industrial or domestic fuel, and allied sectors like petrochemicals, fertilizers and pharmaceuticals. In less than a decade, from 2005 to 2013, India doubled its oil imports from 1.93 million bpd to 3.88 million bpd. India also surpassed Japan to become the world’s third-largest buyer of crude oil, behind only the United States and China. Soon public and private oil companies in India began actively to seek new markets that could meet this rising demand. Today, India is also Asia’s largest heavy crude buyer and home to some of the world’s largest and most complex refineries capable of processing heavy crude, with a refining capacity of roughly 5 million bpd, equal to the refining capacity of Germany, France, and Canada combined.

First and foremost are India’s rapid economic growth and increasing thirst for oil. The first decade of the 21st century saw India’s GDP growing at 7.5 percent on average. This was accompanied by a rising demand for oil, used as transport, industrial or domestic fuel, and allied sectors like petrochemicals, fertilizers and pharmaceuticals. In less than a decade, from 2005 to 2013, India doubled its oil imports from 1.93 million bpd to 3.88 million bpd. India also surpassed Japan to become the world’s third-largest buyer of crude oil, behind only the United States and China. Soon public and private oil companies in India began actively to seek new markets that could meet this rising demand. Today, India is also Asia’s largest heavy crude buyer and home to some of the world’s largest and most complex refineries capable of processing heavy crude, with a refining capacity of roughly 5 million bpd, equal to the refining capacity of Germany, France, and Canada combined.

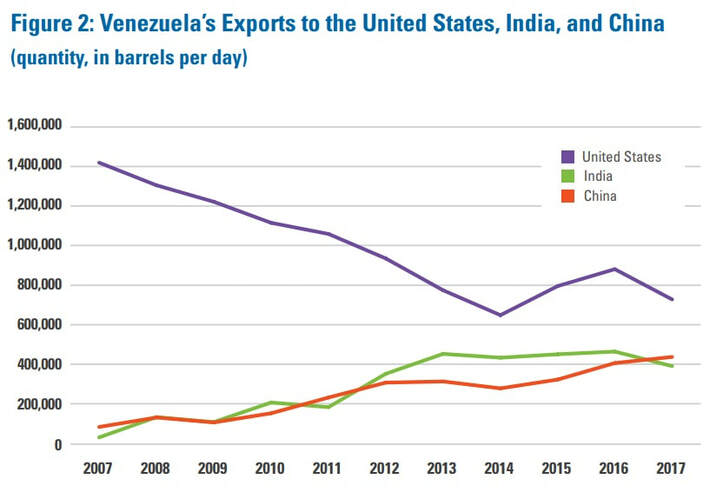

Enter Venezuela, home to the world’s largest proven oil reserves, nearly all of which is in the form of heavy crude. In mid-2007, Venezuela’s then-President Hugo Chávez seized majority stakes in four oil projects in the Orinoco Belt, causing foreign companies like Exxon Mobil and ConocoPhillips to exit the country. Venezuela’s state oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA), assumed more control of operations in the region. The very next year, by 2008, India suddenly became Venezuela’s second-largest export destination, behind only the United States and just a hair’s length ahead of China. Evidently, Venezuela was eager to please in India’s search for new oil suppliers.

Finally, the United States played an inadvertent role in accelerating Venezuela’s trade linkages with India. The mounting pressure of U.S. sanctions on Iran forced India to drastically decrease its oil imports from the Gulf nation. Following U.S. President Barack Obama’s first visit to India in November 2010, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) announced it would stop using the Asian Clearing Union (ACU) to pay for Iranian oil. “Trade transactions with Iran should be settled in any permitted currency outside the ACU mechanism,” noted the RBI in a December 2010 circular. Without the ACU, the threat of U.S. sanctions made it increasingly difficult to settle payments with Iran, leaving a vacuum in India’s oil imports that Venezuela was quick to fill.

Venezuela, which until recently remained in the periphery of India’s economic and political policy, suddenly became a key part of the Indian government’s energy policy in the 21st century. India, too, became vital for Venezuela’s economic survival, accounting for nearly 17 percent of Venezuela’s exports, even more than the country’s exports to China.

Finally, the United States played an inadvertent role in accelerating Venezuela’s trade linkages with India. The mounting pressure of U.S. sanctions on Iran forced India to drastically decrease its oil imports from the Gulf nation. Following U.S. President Barack Obama’s first visit to India in November 2010, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) announced it would stop using the Asian Clearing Union (ACU) to pay for Iranian oil. “Trade transactions with Iran should be settled in any permitted currency outside the ACU mechanism,” noted the RBI in a December 2010 circular. Without the ACU, the threat of U.S. sanctions made it increasingly difficult to settle payments with Iran, leaving a vacuum in India’s oil imports that Venezuela was quick to fill.

Venezuela, which until recently remained in the periphery of India’s economic and political policy, suddenly became a key part of the Indian government’s energy policy in the 21st century. India, too, became vital for Venezuela’s economic survival, accounting for nearly 17 percent of Venezuela’s exports, even more than the country’s exports to China.

|

Overview of India-Venezuela Relations

India and Venezuela established diplomatic relations in 1959, with Venezuela opening its embassy in India in 1962. Soon after, in 1968, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi visited Venezuela as part of an eight-country tour of the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region and decided to open an embassy in Caracas (right). However, bilateral ties stagnated for several years after, as India became preoccupied with domestic issues arising from a period of national emergency during the 1970s; and Venezuela, along with several Latin American countries, entered the so-called ‘lost decade’ of the 1980s, an era marked by high levels of inflation and a serious oil glut, when prices plummeted to less than US$10 per barrel of oil. |

The current phase in bilateral relations began in the early 21st century, with the visit of Chávez to India in March 2005. Chávez’s visit marked the first major overture made by Venezuela to court India as a market for its oil exports. Both countries signed several agreements to deepen cooperation in the hydrocarbons sector—not only for India to buy oil, but also for Indian public sector companies to invest in downstream oil projects in Venezuela.

Chávez’s visit was followed by several high-level exchanges, primarily between the petroleum ministers in both countries. The business of oil has anchored the India-Venezuela relationship, and will continue to do so for many years to come, given the natural convergence between India, one of the largest buyers and consumers of oil, and Venezuela, which has the largest oil reserves in the world.

There are some other, albeit smaller, elements to the India-Venezuela bilateral, which include non-oil related commerce such as pharmaceuticals, automobiles, and textiles, but these exchanges have diminished over the past few years due to the domestic crises that afflict Venezuela.

Overall, the oil business rather than politics drives the bilateral. This, more than anything else, dictates the policy position of both countries. They are both in it for the long run, regardless of which political dispensation is in power in either country. Since business is at the forefront, neither country needs to go out of its way to make political appeasements. Testament to this was India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision to skip the 17th Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) Summit, held in Venezuela on 17 September 2016. Although India’s Vice President led the delegation to the Summit, it was the first time a serving Indian Prime Minister chose not to attend the NAM Summit since the bloc was founded in 1961.

Oil, Oil, and More Oil

Oil, or more specifically, crude petroleum oil, is the cornerstone of India-Venezuela ties. There are very few trade relationships in the world where nearly all trade between two countries is a one-way exchange of just one product—and that is the case for India-Venezuela trade. The export of crude petroleum oil from Venezuela accounted for 98.54 percent of all India-Venezuela trade in 2017/2018 — in comparison, Venezuela’s export of crude petroleum to the United States forms 71 percent of U.S.-Venezuela trade, with the rest comprising U.S. exports to Venezuela. India’s crude oil import capacity, which reached a peak of 4.33 million bpd in 2017, now far exceeds Venezuela’s export capability.

India’s imports of crude oil from Venezuela are partly market-driven, but two other factors are equally if not more important in determining the quantity of imports over the long run:

Going Forward

It is evident that oil is of paramount importance to the India-Venezuela relationship. This became even more pronounced in the face of declining U.S. imports of oil from Venezuela and India’s rising demand for petroleum. Nevertheless, we should note that the India-Venezuela bilateral is unlikely to expand much beyond oil. For Venezuela, and more specifically the current chavista regime, India is not an ideological ally and is unlikely to go out of its way to support Caracas in matters of state and foreign policy. India will remain an invaluable commercial partner for Caracas, as a buyer of oil and supplier of priceless foreign currency in a rapidly plummeting economy.

For India, at least for the short term, Venezuela is only a supplier of oil. But it is becoming a problematic supplier of late due to declining production levels. Besides oil, New Delhi does not see any other strategic imperative in engaging Caracas—it would be ill-advised for India to take any political policy position vis-à-vis Venezuela, especially regarding the ongoing political crises in the country. In light of U.S. sanctions imposed on PDVSA on 28 January 2019, Venezuelan oil exports to the United States could dry up, leaving a shortfall of up to 500,000 bpd that Venezuela exported to the United States before sanctions were imposed. In this scenario, the two private Indian oil companies that currently buy Venezuelan oil, RIL and Nayara Energy, could gradually increase their imports from Venezuela. However, given that both conglomerates, Reliance and Essar, have important business relationships with the United States, it is unclear to what extent they would alter their patterns of trade with Venezuela in response to any pressures from the U.S. government. In some ways, it is advantageous for both countries that the relationship is not burdened by ideology. This is unlike Venezuela’s allies China and Russia, who remain close to the current administration. But oil will continue to flow from Venezuela to India in roughly similar measures regardless of the party in power in either country.

In the short term, due to Venezuela’s near-total economic collapse—with an economy shrinking by 9.9 percent in 2018, inflation at 1,365,323 percent and oil output possibly falling below 1 million bpd in 2019 — India will have to look elsewhere to make up the shortfall in oil supplies. But in the long run, the fortunes of both countries are inescapably tied together. Venezuela’s economy is bound to recover eventually, especially if global oil prices rise in the short and medium term. According to a December 2018 report by Oxford Economics, the country’s GDP is forecast to grow by 4.6 percent and exports by 11.9 percent in 2021. This potential economic recovery, coupled with increased oil production, will be favorable to India-Venezuela ties and most likely result in an increase in Venezuelan oil exports to India.

Venezuela forms an integral part of India’s overall energy security policy, which includes cooperation with other oil-producing nations in Africa (such as Nigeria and Angola) and Central Asia (like Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan). As a result, African countries now account for about 18 percent of India’s total crude oil imports. In the long run, New Delhi’s energy diplomacy with Africa and Central Asia is likely to run parallel to India-Venezuela ties, without having a negative impact on the bilateral. Oil produced from these regions tend to be of lighter grades, and are therefore priced much higher than Venezuelan heavy crude. Moreover, these countries possess much smaller reserves of crude oil—even Nigeria, which currently exports nearly as much oil to India as Venezuela does, has 37 billion barrels of oil reserves, only about 12 percent of Venezuela’s oil reserves.

Despite India’s dire need to increase the proportion of renewables in its energy matrix, petroleum oil will continue to be indispensable at least for another half-century. Even the most ambitious estimates by the government of India put India’s oil import demand between 7.19 million bpd and 9.34 million bpd by 2040, assuming that renewables account for a full ten-fold increase from their current level in the energy matrix. If Venezuela is to continue to provide roughly 10 percent of India’s oil needs in 2040, this means exports would have to increase from the current average of 424,000 bpd to between 702,000 bpd and 924,000 bpd. This alone should provide impetus for both countries to maintain a stable and cordial relationship.

Chávez’s visit was followed by several high-level exchanges, primarily between the petroleum ministers in both countries. The business of oil has anchored the India-Venezuela relationship, and will continue to do so for many years to come, given the natural convergence between India, one of the largest buyers and consumers of oil, and Venezuela, which has the largest oil reserves in the world.

There are some other, albeit smaller, elements to the India-Venezuela bilateral, which include non-oil related commerce such as pharmaceuticals, automobiles, and textiles, but these exchanges have diminished over the past few years due to the domestic crises that afflict Venezuela.

Overall, the oil business rather than politics drives the bilateral. This, more than anything else, dictates the policy position of both countries. They are both in it for the long run, regardless of which political dispensation is in power in either country. Since business is at the forefront, neither country needs to go out of its way to make political appeasements. Testament to this was India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision to skip the 17th Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) Summit, held in Venezuela on 17 September 2016. Although India’s Vice President led the delegation to the Summit, it was the first time a serving Indian Prime Minister chose not to attend the NAM Summit since the bloc was founded in 1961.

Oil, Oil, and More Oil

Oil, or more specifically, crude petroleum oil, is the cornerstone of India-Venezuela ties. There are very few trade relationships in the world where nearly all trade between two countries is a one-way exchange of just one product—and that is the case for India-Venezuela trade. The export of crude petroleum oil from Venezuela accounted for 98.54 percent of all India-Venezuela trade in 2017/2018 — in comparison, Venezuela’s export of crude petroleum to the United States forms 71 percent of U.S.-Venezuela trade, with the rest comprising U.S. exports to Venezuela. India’s crude oil import capacity, which reached a peak of 4.33 million bpd in 2017, now far exceeds Venezuela’s export capability.

India’s imports of crude oil from Venezuela are partly market-driven, but two other factors are equally if not more important in determining the quantity of imports over the long run:

- Heavy crude: As the name suggests, heavy crude tends to be thicker and denser, with more sulfur, metals, nitrogen, and other contaminants. It is generally defined as oil with an API gravity of 22.3° or less. Extra heavy crude has an API gravity of less than 10°, which means it sinks rather than floats in water. Heavy crude goes through a more complex refining process, where contaminants like sulfur are removed. In 2009, a U.S. Geological Survey team published a paper estimating “a mean volume of 513 billion barrels of technically recoverable heavy oil in the Orinoco Oil Belt Assessment Unit of the East Venezuela Basin Province; the range is 380 to 652 billion barrels.” Even at a much lower estimate of 224 billion barrels of heavy crude oil, Venezuela’s Orinoco Belt contains about the same amount of oil as all of North America. Many large Indian refineries are capable of processing heavy Venezuelan crude, which is priced much lower than lighter grades of crude due to the complex refining process it must undergo. The Venezuelan Merey, a heavy crude with an API gravity of 16°, traded at US$69.31 in September 2018, a whole 12 percent less than the Brent Crude price of US$78.80. This poses an advantage for Indian refiners that can turn a profit converting heavy crude to finished products like gasoline or diesel and sell it on the open market. India and Venezuela therefore enjoy a synergy with heavy crude, which matters even more in the long run as technology makes heavy crude easier and cheaper to extract, transport, and refine.

- India’s diversification policy: Although India produces a fair amount of oil, at about 803,000 bpd in 2017, this accounts for only about 18 percent of the total oil consumption of 4.46 million bpd, the remainder of which is imported. Historically, much of this oil requirement has been met by the Middle East; the region is so close that goods can transit in as little as three to four days from the Middle East to the west coast of India. In comparison, it can take from 40 to 60 days for a ship to sail from Venezuela to India. Naturally, the Middle East is the most important source of oil for India; in 2007, more than 75 percent of India’s oil imports came from the region. But it can be a risky proposition to depend on one region for such an important and strategic resource. The government of India thus actively seeks to diversify oil import sources. India’s Oil Minister Dharmendra Pradhan confirmed: “Procurement has to be diversified, taking into account the changing geopolitics in the world. I met a representative from the U.S. government recently and I have asked for oil from them…. We will also look to Russia and Latin America if that suits our needs.”This diversification policy has shown rather quick results. In 2014 and 2015, the Middle East only supplied 59 percent of India’s oil imports, a whole 16 percentage points less than it did in 2007; Latin American countries like Venezuela, Mexico, and Brazil, as well as African nations like Nigeria and Angola, made up the rest. As India’s demand for oil increases, it will open the trade basket for more suppliers, including the United States, which has already started supplying crude oil to India—in 2017, the United States exported about $470 million worth of crude oil to India, and that has increased to $2.6 billion for January to November 2018. Here too, there is great synergy with Venezuela: in addition to India’s diversification of oil import sources, Venezuela needs to capture large new markets given that its largest customer, the United States, rapidly cut oil imports due primarily to an increase in domestic oil and gas production and then to U.S. financial and, subsequently, oil sanctions. U.S. oil imports from Venezuela decreased from 1.4 million bpd in 2007 to about half of that in 2017. The Venezuelan government’s Plan Siembra Petrolera 2005–2030 (Sowing the Oil Plan) names India, along with other Asian nations like China and Japan, as key markets for export diversification.

Going Forward

It is evident that oil is of paramount importance to the India-Venezuela relationship. This became even more pronounced in the face of declining U.S. imports of oil from Venezuela and India’s rising demand for petroleum. Nevertheless, we should note that the India-Venezuela bilateral is unlikely to expand much beyond oil. For Venezuela, and more specifically the current chavista regime, India is not an ideological ally and is unlikely to go out of its way to support Caracas in matters of state and foreign policy. India will remain an invaluable commercial partner for Caracas, as a buyer of oil and supplier of priceless foreign currency in a rapidly plummeting economy.

For India, at least for the short term, Venezuela is only a supplier of oil. But it is becoming a problematic supplier of late due to declining production levels. Besides oil, New Delhi does not see any other strategic imperative in engaging Caracas—it would be ill-advised for India to take any political policy position vis-à-vis Venezuela, especially regarding the ongoing political crises in the country. In light of U.S. sanctions imposed on PDVSA on 28 January 2019, Venezuelan oil exports to the United States could dry up, leaving a shortfall of up to 500,000 bpd that Venezuela exported to the United States before sanctions were imposed. In this scenario, the two private Indian oil companies that currently buy Venezuelan oil, RIL and Nayara Energy, could gradually increase their imports from Venezuela. However, given that both conglomerates, Reliance and Essar, have important business relationships with the United States, it is unclear to what extent they would alter their patterns of trade with Venezuela in response to any pressures from the U.S. government. In some ways, it is advantageous for both countries that the relationship is not burdened by ideology. This is unlike Venezuela’s allies China and Russia, who remain close to the current administration. But oil will continue to flow from Venezuela to India in roughly similar measures regardless of the party in power in either country.

In the short term, due to Venezuela’s near-total economic collapse—with an economy shrinking by 9.9 percent in 2018, inflation at 1,365,323 percent and oil output possibly falling below 1 million bpd in 2019 — India will have to look elsewhere to make up the shortfall in oil supplies. But in the long run, the fortunes of both countries are inescapably tied together. Venezuela’s economy is bound to recover eventually, especially if global oil prices rise in the short and medium term. According to a December 2018 report by Oxford Economics, the country’s GDP is forecast to grow by 4.6 percent and exports by 11.9 percent in 2021. This potential economic recovery, coupled with increased oil production, will be favorable to India-Venezuela ties and most likely result in an increase in Venezuelan oil exports to India.

Venezuela forms an integral part of India’s overall energy security policy, which includes cooperation with other oil-producing nations in Africa (such as Nigeria and Angola) and Central Asia (like Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan). As a result, African countries now account for about 18 percent of India’s total crude oil imports. In the long run, New Delhi’s energy diplomacy with Africa and Central Asia is likely to run parallel to India-Venezuela ties, without having a negative impact on the bilateral. Oil produced from these regions tend to be of lighter grades, and are therefore priced much higher than Venezuelan heavy crude. Moreover, these countries possess much smaller reserves of crude oil—even Nigeria, which currently exports nearly as much oil to India as Venezuela does, has 37 billion barrels of oil reserves, only about 12 percent of Venezuela’s oil reserves.

Despite India’s dire need to increase the proportion of renewables in its energy matrix, petroleum oil will continue to be indispensable at least for another half-century. Even the most ambitious estimates by the government of India put India’s oil import demand between 7.19 million bpd and 9.34 million bpd by 2040, assuming that renewables account for a full ten-fold increase from their current level in the energy matrix. If Venezuela is to continue to provide roughly 10 percent of India’s oil needs in 2040, this means exports would have to increase from the current average of 424,000 bpd to between 702,000 bpd and 924,000 bpd. This alone should provide impetus for both countries to maintain a stable and cordial relationship.