Today’s obsessive pursuit of natural resources is part of a centuries-long scientific quest to identify and understand the elements that make up the earth.

The 17 rare earth elements, or lanthanides, consist of elements 21 (scandium), 39 (yttrium), and 57 (lanthanum) to 71 (lutetium). The rare earths were so named because of their low concentration in minerals which were scarce. However, some of the elements are not as rare as once thought. Today, the rare earths are important for their use in hard drives and wind turbine generators, glass polishes, ceramic glazes, protective goggles, lasers and superconductors. More recently, some have been used in diagnostic imaging in the field of nuclear medicine.

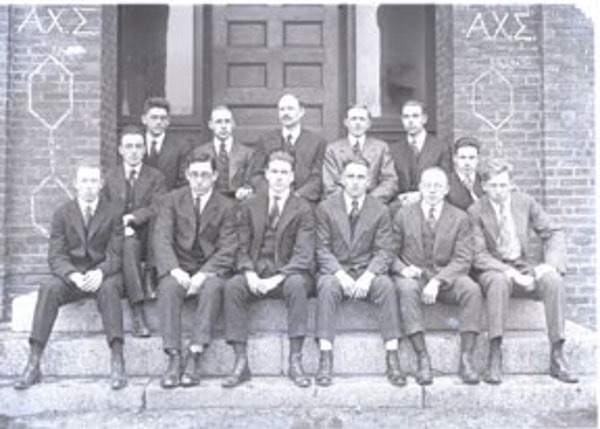

A University of New Hampshire (UNH) professor, Charles James (1880-1928), all but forgotten today, was well known and highly respected by his contemporaries for his contribution to rare earth chemistry. The very first paper published by James in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, "A New Method for the Separation of the Yttrium Earths," indicates the direction of his research. Keenly motivated to improve the methods of separation and endowed with imagination and determination, James experimented with the preparation of many different salts of the rare earths derived from simple inorganic to complex organic acids. Letters in the UNH archives show that he supplied numerous workers worldwide with samples of the compounds that he had prepared, including the sample of terbium that Henry Moseley, an English scientist, used to determine its atomic number. James's use of bromates and double magnesium nitrates for fractional crystallization became known as the "James Method." Developed in the early 1900s, his method was used widely by others and remained the best for separating rare earth elements until the advent of ion exchange in the 1940s.

James's work with the rare earths is part of a long history that illuminates more areas of chemical progress than does any other group of elements. It stretches from the discovery of the first rare earth mineral in 1787 by Carl Axel Arrhenius to the unequivocal identification of the last in 1947 by Jacob Marinsky, Lawrence Glendenin and Charles Coryell. The story involves the discovery of emission spectroscopy by Gustav Robert Kirchhoff and Robert Wilhelm Bunsen, the development of the periodic table by Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev and Lothar Meyer, and the discovery of X-rays by Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen. It includes the formulation of atomic numbers by Moseley, atomic structure by Neils Bohr and Ernest Rutherford, and work on the atomic bomb during World War II. Over the course of a century, two minerals — ytterbite and cerite — were separated into eight and seven stable elements, respectively.

The story of their discovery is probably the most confusing and complex of any of the elements. The search for and identification of the rare earth elements constituted an integral part of the development of science and technology in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Several factors made their identification difficult: The chemical and physical properties of the different elements are quite similar; the elements were isolated as "earths" or oxides of the elements; and the methods of separation and purification depended on laborious fractional precipitation and crystallization techniques. Compounding the difficulties of separation were a lack of good methods for identification and assessment of purity and a lack of knowledge of the number of rare earth elements that existed.

The first rare earth element, yttrium, was isolated in 1794 by the Swedish chemist Johan Gadolin from a heavy black mineral, ytterbite, named for the village of Ytterby where it was found. In 1803, Jons Jacob Berzelius and Wilhelm Hisinger in Sweden and Martin Klaproth in Germany announced almost simultaneously that they had isolated a new element, cerium, from the mineral cerite. This provoked the first of several priority disputes in the pathway to the discovery of rare earth elements.

The invention of the spectroscope by Kirchhoff and Bunsen in 1859 and the development of spectral analysis, along with the development of the periodic table by Mendeleev and Meyer in 1869, provided valuable tools for the study of rare earths. The impact of these advances is clear. In the 60 or so years before their introduction, only six rare earths had been identified, one of them erroneously. In the following 50 years, the number jumped to 15. However, problems remained. The rare earths severely challenged Mendeleev's periodic system, because he did not know where to place them in the table. He made many modifications to accommodate them. Meanwhile, spectroscopic analysis was causing difficulties.

Because of the complexity of the spectra of the rare earths and the questionable purity of the samples, many claims were being made for new elements that proved false. Despite these difficulties, by 1901 only two rare earths were still undiscovered. In 1907, almost simultaneously, Georges Urbain in France, Carl Auer von Welsbach in Austria and Charles James in the United States separated ytterbium into two fractions. Urbain's designation of the new element as lutetium, after the Roman name for his native city, Paris, was accepted by most, although von Welsbach's name cassiopium was used in German-speaking countries for many years. Von Welsbach contested Urbain's priority for the discovery of lutetium. James, although he had accumulated a substantial amount of highly purified lutetium oxide, withdrew a paper he had submitted for publication and made no public claim for his own work.

Lutetium was the 16th of the rare earths to be identified. Using X-ray spectroscopy, Moseley demonstrated that only one rare earth element remained to be discovered: element 61. He determined the atomic numbers of the elements and showed that they were arranged in the periodic table in order of atomic number, not atomic weight, as Mendeleev had thought. In the 1920s, James, B. Smith Hopkins and Luigi Rolla each thought he had isolated element 61. Hopkins's publication preceded that of James, and so Hopkins's designation of the element as illinium was accepted temporarily. The last of the priority disputes over discovery of a rare earth element ended inconclusively, however, when none of the claims could be substantiated. The authentic discovery of element 61 had to await the development of a new separation technique, ion-exchange chromatography, and work on the atomic bomb during World War II. Finally, in 1947, Marinsky, Glendenin and Coryell announced the discovery of the unstable element 61, which they named promethium after the Titan who stole fire from the gods.

A University of New Hampshire (UNH) professor, Charles James (1880-1928), all but forgotten today, was well known and highly respected by his contemporaries for his contribution to rare earth chemistry. The very first paper published by James in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, "A New Method for the Separation of the Yttrium Earths," indicates the direction of his research. Keenly motivated to improve the methods of separation and endowed with imagination and determination, James experimented with the preparation of many different salts of the rare earths derived from simple inorganic to complex organic acids. Letters in the UNH archives show that he supplied numerous workers worldwide with samples of the compounds that he had prepared, including the sample of terbium that Henry Moseley, an English scientist, used to determine its atomic number. James's use of bromates and double magnesium nitrates for fractional crystallization became known as the "James Method." Developed in the early 1900s, his method was used widely by others and remained the best for separating rare earth elements until the advent of ion exchange in the 1940s.

James's work with the rare earths is part of a long history that illuminates more areas of chemical progress than does any other group of elements. It stretches from the discovery of the first rare earth mineral in 1787 by Carl Axel Arrhenius to the unequivocal identification of the last in 1947 by Jacob Marinsky, Lawrence Glendenin and Charles Coryell. The story involves the discovery of emission spectroscopy by Gustav Robert Kirchhoff and Robert Wilhelm Bunsen, the development of the periodic table by Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev and Lothar Meyer, and the discovery of X-rays by Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen. It includes the formulation of atomic numbers by Moseley, atomic structure by Neils Bohr and Ernest Rutherford, and work on the atomic bomb during World War II. Over the course of a century, two minerals — ytterbite and cerite — were separated into eight and seven stable elements, respectively.

The story of their discovery is probably the most confusing and complex of any of the elements. The search for and identification of the rare earth elements constituted an integral part of the development of science and technology in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Several factors made their identification difficult: The chemical and physical properties of the different elements are quite similar; the elements were isolated as "earths" or oxides of the elements; and the methods of separation and purification depended on laborious fractional precipitation and crystallization techniques. Compounding the difficulties of separation were a lack of good methods for identification and assessment of purity and a lack of knowledge of the number of rare earth elements that existed.

The first rare earth element, yttrium, was isolated in 1794 by the Swedish chemist Johan Gadolin from a heavy black mineral, ytterbite, named for the village of Ytterby where it was found. In 1803, Jons Jacob Berzelius and Wilhelm Hisinger in Sweden and Martin Klaproth in Germany announced almost simultaneously that they had isolated a new element, cerium, from the mineral cerite. This provoked the first of several priority disputes in the pathway to the discovery of rare earth elements.

The invention of the spectroscope by Kirchhoff and Bunsen in 1859 and the development of spectral analysis, along with the development of the periodic table by Mendeleev and Meyer in 1869, provided valuable tools for the study of rare earths. The impact of these advances is clear. In the 60 or so years before their introduction, only six rare earths had been identified, one of them erroneously. In the following 50 years, the number jumped to 15. However, problems remained. The rare earths severely challenged Mendeleev's periodic system, because he did not know where to place them in the table. He made many modifications to accommodate them. Meanwhile, spectroscopic analysis was causing difficulties.

Because of the complexity of the spectra of the rare earths and the questionable purity of the samples, many claims were being made for new elements that proved false. Despite these difficulties, by 1901 only two rare earths were still undiscovered. In 1907, almost simultaneously, Georges Urbain in France, Carl Auer von Welsbach in Austria and Charles James in the United States separated ytterbium into two fractions. Urbain's designation of the new element as lutetium, after the Roman name for his native city, Paris, was accepted by most, although von Welsbach's name cassiopium was used in German-speaking countries for many years. Von Welsbach contested Urbain's priority for the discovery of lutetium. James, although he had accumulated a substantial amount of highly purified lutetium oxide, withdrew a paper he had submitted for publication and made no public claim for his own work.

Lutetium was the 16th of the rare earths to be identified. Using X-ray spectroscopy, Moseley demonstrated that only one rare earth element remained to be discovered: element 61. He determined the atomic numbers of the elements and showed that they were arranged in the periodic table in order of atomic number, not atomic weight, as Mendeleev had thought. In the 1920s, James, B. Smith Hopkins and Luigi Rolla each thought he had isolated element 61. Hopkins's publication preceded that of James, and so Hopkins's designation of the element as illinium was accepted temporarily. The last of the priority disputes over discovery of a rare earth element ended inconclusively, however, when none of the claims could be substantiated. The authentic discovery of element 61 had to await the development of a new separation technique, ion-exchange chromatography, and work on the atomic bomb during World War II. Finally, in 1947, Marinsky, Glendenin and Coryell announced the discovery of the unstable element 61, which they named promethium after the Titan who stole fire from the gods.

Excerpted from the article “Separation of Rare Earth Elements by Charles James” with permission from the American Chemical Society. The American Chemical Society’s National Historic Chemical Landmarks program honors seminal achievements in the history of the chemical sciences and provides a record of their contributions to chemistry and society.