|

The history of plastic and of the very idea of disposability suggest that we and the planet have become victims of plastic’s success. Synthetic materials took over our economy, our lifestyles, and our imaginations because they did their jobs so well. How did we get to this point?

In 1957 Disneyland opened the Monsanto House of the Future, an all-plastic dwelling. Over the next 10 years millions of visitors passed through its fantastical rooms, designed by MIT architects with curved walls and large windows. The house was equipped with plastic chairs and plastic floors, the kitchen with precise stacks of plastic plates and plastic cups. Monsanto’s house trumpeted the wonders of science, as well as the chemical industry and its products. Plastic, it proclaimed, was the material of tomorrow. |

Tomorrow has come, and plastic is everywhere. In the half century since the Monsanto house closed, plastic has conquered the planet: globally, we now consume a million plastic bottles a minute and more than a trillion plastic bags every year.

Nobody lives in curved plastic rooms, but synthetic carpeting, vinyl flooring and laminate counters are all commonplace. And most Americans’ daily routines depend on single-use items and throwaway plastic packaging, much of it flowing into streams and oceans, polluting our ecosystems. Tiny plastic fragments, off-gassing and effluents from plastic factories pollute our bodies. The plastic dream has become a plastic nightmare.

Nobody lives in curved plastic rooms, but synthetic carpeting, vinyl flooring and laminate counters are all commonplace. And most Americans’ daily routines depend on single-use items and throwaway plastic packaging, much of it flowing into streams and oceans, polluting our ecosystems. Tiny plastic fragments, off-gassing and effluents from plastic factories pollute our bodies. The plastic dream has become a plastic nightmare.

Disposability

Disposability is not a new idea. Toilet paper was common by 1900; paper cups and paper towels were adopted as sanitary measures in public places during the following decades, though few were yet used in homes. Disposable razor blades and bottle caps came into common use around the same time.

But most Americans produced little trash, practicing habits of reuse that had prevailed in agricultural communities. They made soup from food scraps or fed them to animals; objects worthless to adults became playthings for children. People spent considerable time and effort taking care of things – oiling and waxing, mending and altering, working to prolong the useful lives of the things they owned.

Disposability is not a new idea. Toilet paper was common by 1900; paper cups and paper towels were adopted as sanitary measures in public places during the following decades, though few were yet used in homes. Disposable razor blades and bottle caps came into common use around the same time.

But most Americans produced little trash, practicing habits of reuse that had prevailed in agricultural communities. They made soup from food scraps or fed them to animals; objects worthless to adults became playthings for children. People spent considerable time and effort taking care of things – oiling and waxing, mending and altering, working to prolong the useful lives of the things they owned.

|

By the 1920s, most families were moving toward a modern relationship to the material world. Convenience and cleanliness came to symbolize the goals of a modern lifestyle, a synonym for luxury, comfort and emancipation from worry and work.

Bakelite, the first plastic produced entirely from synthetic materials, was invented in 1907. By the beginning of the second world war, plastic was commonly accepted for industrial parts, automobile distributor caps and colorful costume jewelry. The chemical industry was widely celebrated for plastic’s contributions to the war effort – nylon parachutes and ripcords, plastic airplane windshields, synthetic rubber wing linings. As soon as the war ended, major chemical companies pivoted from war production to consumer goods – DuPont, for instance, reconverted its factories to produce yarn for nylon stockings instead of parachutes. |

People did not yet regard plastics as disposable. Indeed, most new synthetic materials were touted as indestructible. They replaced breakables such as ceramics and glass, and natural materials that deteriorated over time, such as wood, metal, cork and animal hides. Postwar construction incorporated durable new plastic floorings and countertops. In the kitchens and bathrooms of newly built suburbs, women tossed trash in plastic waste baskets and powdered their noses using plastic compacts.

|

Hyperbolic Language

By the 1960s, long-lasting plastics had been joined by plastic throwaways, including Saran Wrap, its more affordable competitors, and early plastic packaging. Shampoo came in glass bottles when I was a child in the 50s, but when plastic bottles came along we could stop washing our hair in fear of bloody feet in the shower. Plastics were advertised in hyperbolic language. “Bottle magic,” Dew deodorant crowed about its new squeeze bottle that “can’t leak, break, or spill”. LePage’s liquid plastic glue offered “amazing strength and durability”. |

... when plastic bottles came along we could stop washing our hair in fear of bloody feet in the shower.

|

From the manufacturer’s standpoint, the raw materials and fabrication processes were cheap and the finished goods lightweight. Consumers adopted synthetic materials gratefully because they were so effective. As Barry Commoner, one of the 20th century’s greatest environmental thinkers, explained in his 1971 bestseller, The Closing Circle: “Plastics clutter the landscape because they are unnatural, synthetic substances designed to resist degradation – precisely the properties that are the basis of their technological value.”

The new materials offered freedom from attention, care and responsibility for material things. They cut down on laundry, cleaning and dishwashing chores. A spotlessness and ease once attainable only with servants could now be achieved by buying things and by throwing things away.

The new materials offered freedom from attention, care and responsibility for material things. They cut down on laundry, cleaning and dishwashing chores. A spotlessness and ease once attainable only with servants could now be achieved by buying things and by throwing things away.

|

The transition to a throwaway consumer culture was complex and gradual: the young and the wealthy embraced new products first, while others lived as they always had. But eventually the shift was complete as people lost the knowledge of how to make things last, and the leftovers and scraps they might once have valued became trash instead.

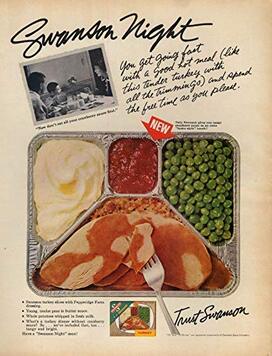

Eventually an actual celebration of trashmaking emerged. As frozen foods were introduced during the 1950s, disposable packaging became an all-in-one problem solver: the Swanson brand frozen TV dinner and products from competitors like Banquet and Morton replaced pots, pans and plates, eliminating the need for dishwashing as well as cooking. At first, many consumers, unused to a throwaway lifestyle, washed them anyhow. My family amassed quite a collection of tins from frozen pot pies, the dinner of choice when my parents went out for the evening. |

But soon more and more products were manufactured and sold with an understanding that they would soon be trash. Disposability rested on the ideas that somebody else would carry away the trash, that used materials were worthless, and that nobody need think about what happened to them.

Plastic became the basis for a new relationship to the material world: it required consumers to buy things rather than make them, to throw things out rather than fix them. Nobody made plastic at home, hardly anybody understood how it was made, it usually could not be repaired, and there was no way to return it to nature.

Plastic became the basis for a new relationship to the material world: it required consumers to buy things rather than make them, to throw things out rather than fix them. Nobody made plastic at home, hardly anybody understood how it was made, it usually could not be repaired, and there was no way to return it to nature.

Single-Use Tsunami

On the first Earth Day in 1970, Americans were using nowhere near the level of plastics we now take for granted. The microwave oven had not yet taken off and frozen foods were still in foil, ketchup still came in glass bottles, and the shift from paper to plastic at the grocery store was more than a decade away. But the new materials spawned by the chemical industry had become normalized, and consumers generally appreciated and applauded them. The corporations that made consumer goods encouraged us to keep on buying, enriching those companies – as well as the chemical manufacturers, such as Monsanto, Dow and DuPont, and the fossil fuel industry.

Recent years have brought a tsunami of single-use plastics (straws, plastic bags, takeout containers, plastic water bottles). Nearly half the plastic ever produced has been manufactured since 2000. Even though many people alive today can remember a world without ubiquitous plastic, we still have a hard time remembering how we actually lived without it.

On the first Earth Day in 1970, Americans were using nowhere near the level of plastics we now take for granted. The microwave oven had not yet taken off and frozen foods were still in foil, ketchup still came in glass bottles, and the shift from paper to plastic at the grocery store was more than a decade away. But the new materials spawned by the chemical industry had become normalized, and consumers generally appreciated and applauded them. The corporations that made consumer goods encouraged us to keep on buying, enriching those companies – as well as the chemical manufacturers, such as Monsanto, Dow and DuPont, and the fossil fuel industry.

Recent years have brought a tsunami of single-use plastics (straws, plastic bags, takeout containers, plastic water bottles). Nearly half the plastic ever produced has been manufactured since 2000. Even though many people alive today can remember a world without ubiquitous plastic, we still have a hard time remembering how we actually lived without it.

|

Even early on, the drawbacks were evident. In 1971, Commoner described the proliferation of plastic in the oceans – fragments of plastic ropes and nets. “These pollution problems arise not out of some minor inadequacies in the new technologies, but because of their very success in accomplishing their designed aims.”

None of us live in exactly the future that the Monsanto House designers envisioned, but plastic has indeed become the defining material of our time. Recycling plastic turns out to be considerably more complex and technical than turning rags into paper or melting down metals. Producing plastic continues to create potential hazards that emerge as threats to public health. In exchange for indestructible, non-permeable solutions to everyday problems, as Commoner warned, “we have created for ourselves a new and dangerous world.” |

Susan Strasser is an award-winning historian, a Distinguished Lecturer for the Organization of American Historians, and Richards Professor of American History Emerita at the University of Delaware. Her books include Never Done: A History of American Housework, Satisfaction Guaranteed: The Making of the American Mass Market, and Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash.

Republished with permission from the original article, “Never gonna give you up: how plastic seduced America.”