The importance of recent explosions targeted at Saudi Arabian oil infrastructure should not be exaggerated, but not downplayed either. Any given attack is unlikely to do more than temporary damage, as the industry is typically able to circumvent or overcome problems in ways not obvious in advance. The Kuwaiti oil field fires were put out far quicker than presumed, for example, as people on the ground were more inventive than distant analysis. Still, there is certainly a threat of greater supply disruptions down the line, given the heightened tensions in the Gulf.

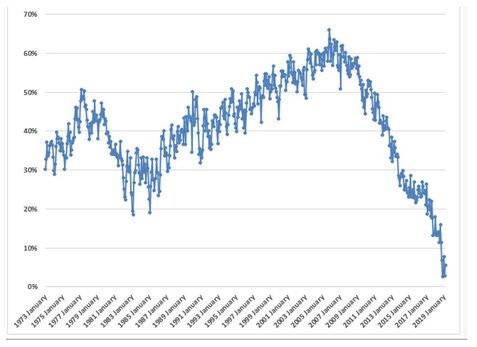

Unfortunately, the shale boom, which has nearly made the U.S. independent on oil imports, suggests to many that the nation is “energy independent” and doesn’t need to care what happens in the Mideast oil sector. Nothing could be further from the truth, which emphasizes one of the many myths surrounding energy security, the common obsession with volumes or barrels. As the figure shows, US net imports are very small now, which might seem to imply U.S. invulnerability to oil crises but this is just as false as the earlier thinking that imports reaching 50% of demand would somehow be catastrophic. That date came and went quietly, just as if a hundred pundits hadn’t predicted the apocalypse.

Unfortunately, the shale boom, which has nearly made the U.S. independent on oil imports, suggests to many that the nation is “energy independent” and doesn’t need to care what happens in the Mideast oil sector. Nothing could be further from the truth, which emphasizes one of the many myths surrounding energy security, the common obsession with volumes or barrels. As the figure shows, US net imports are very small now, which might seem to imply U.S. invulnerability to oil crises but this is just as false as the earlier thinking that imports reaching 50% of demand would somehow be catastrophic. That date came and went quietly, just as if a hundred pundits hadn’t predicted the apocalypse.

After the first oil crisis in 1973, the common refrain was that governments had a duty to prevent factories from going dark and houses from going cold. Especially in Europe, some governments sought to ensure they had adequate supply for industry and the public regardless of cost (or diplomatic concessions). Unfortunately, the factories went dark and houses went cold because soaring prices created a recession.

|

The misconception persists, as when during the first Gulf War the Bush Administration (41) argued against releasing oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) until there were physical shortages. None really occurred because prices balanced the market, just as economic theory predicts. But higher prices (although they didn’t get that high in 1991) were treated as inconsequential, despite the economic damage.

|

"If a major supply disruption were to occur now, when surplus capacity is pretty low, oil prices would soar and the fact that we import very little would mean our import bill would be reduced, but the economy as a whole would still suffer."

|

This conflicts with the opposite urge, which is to use the SPR whenever prices rise. This would be a worse mistake than not using the SPR during an oil supply disruption, as it could easily morph into government attempts to manage prices, something that always tempts politicians. But tight markets need to be cured by higher prices, not supplemental or surge supplies. Venezuelan attempts to regulate prices might seem so absurd as to not be relevant, but past U.S. price controls on oil and natural gas had serious negative effects, including raising oil imports and creating shortages of natural gas.

|

If a major supply disruption were to occur now, when surplus capacity is pretty low, oil prices would soar and the fact that we import very little would mean our import bill would be reduced, but the economy as a whole would still suffer. The industry and the Southwest would benefit greatly, but most other consumers would have much less money. A 50% increase in gasoline prices would take about $130 billion out of consumers’ pockets, wiping out the recent tax cuts. Jack Daniels sales might soar, but that wouldn’t do much for the New England economy.

This is not a criticism of the shale industry which has made a huge contribution to the U.S. (and world) economy as well as reducing greenhouse gas emissions more than most countries with green postures. But we shouldn’t think we’re isolated from the world oil market: we’re better off now than when imports passed 60%, but it’s a matter of being safer not safe. |

The original article was published in Forbes.

Michael Lynch spent nearly 30 years at MIT as a student and then researcher at the Energy Laboratory and Center for International Studies. Other past positions include being the chief energy economist at what is now IHS Global Insight, and the president of the US Association for Energy Economics. Currently, Lynch is president of Strategic Energy and Economic Research, Inc. and the author of "The Peak Oil Scare and the Coming Oil Flood," published by Praeger.

Michael Lynch spent nearly 30 years at MIT as a student and then researcher at the Energy Laboratory and Center for International Studies. Other past positions include being the chief energy economist at what is now IHS Global Insight, and the president of the US Association for Energy Economics. Currently, Lynch is president of Strategic Energy and Economic Research, Inc. and the author of "The Peak Oil Scare and the Coming Oil Flood," published by Praeger.