I was among the hundreds of thousands of Northern California residents who were without power. I got off easy; power went out on a Wednesday night and was restored by the time I got home from work on Thursday. Really no big deal. Some food had to be thrown out; but I could charge my phone in the car and had plenty of batteries and bottles of water.

Pacific Gas and Electric — whose faulty equipment was partially to blame for the deadly wildfires of the last two years — determined wind gusts were going to be strong and humidity levels low, thus creating conditions for a potential round of blazes. I don’t begrudge them for trying to save lives; they’re up against a changing climate and our new normal.

And having only been back from Congo for a week, much of my three weeks in Africa was spent in areas with little or no electricity or running water. Nick and I were constantly rigging up ways to charge our phones, laptop and camera batteries. Bucket baths were de rigueur. And we saw Chinese- and German-made solar panels everywhere, from smaller Etch-a-Sketch-sized panels thrown up on the thatched raffia of mud huts, to larger panels powering up beauty salons.

Solar powers this small barber shop/beauty salon in Kamponde, Congo

We purchased a small gasoline-powered, Indian-made generator in Kananga for 150 bucks to take to Kamponde so that we would always have a way to charge our phones and batteries. I ended up leaving it behind for the Catholic nuns. In one of the rare news stories out of the Kasai region of Congo, I had learned a few weeks before we left for the DRC that the nuns and parish priest had been robbed at gunpoint; cellphones and salaries for their teachers stolen. So now these hardworking sisters — who run a school, farm and take care of orphans, all without the luxury of electricity — now also had no way to communicate outside of the village.

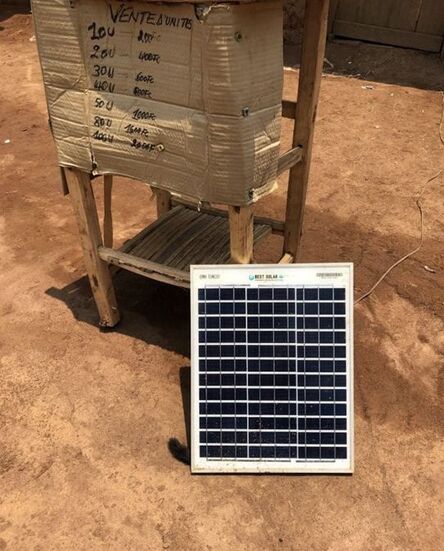

And when our generator ran out of petrol, I sent my laptop to a little shop where I paid about $2 to get it fully charged in about three hours using a solar panel. Incredible progress for a small village where, only 13 years ago, there was no solar power or cellular tower.

“Solar power and wireless communications are made for Africa, because we don’t have the infrastructure,” says my old friend Jim Mukenge, a Kananga-based politician who helped me organize this great, exhausting adventure and traveled with me to Kamponde. “The cheap solar panels and LED bulbs now coming from China are a blessing,” Jim told me. “In all the villages now, everybody has a little panel. They can have a little light; they can play their music. And they can they can charge phones and have a little income.”

“They can feel like they’re part of the modern world.”

And when our generator ran out of petrol, I sent my laptop to a little shop where I paid about $2 to get it fully charged in about three hours using a solar panel. Incredible progress for a small village where, only 13 years ago, there was no solar power or cellular tower.

“Solar power and wireless communications are made for Africa, because we don’t have the infrastructure,” says my old friend Jim Mukenge, a Kananga-based politician who helped me organize this great, exhausting adventure and traveled with me to Kamponde. “The cheap solar panels and LED bulbs now coming from China are a blessing,” Jim told me. “In all the villages now, everybody has a little panel. They can have a little light; they can play their music. And they can they can charge phones and have a little income.”

“They can feel like they’re part of the modern world.”

|

Counting My Blessings

We take for granted our modern devices and utilities in this country — and I’m as spoiled as the next girl. I shuddered at the thought of taking a cold shower once my power went out — only weeks after I had taken dozens of chilly bucket baths. Granted, it was steaming hot in Congo and we’re into Fall weather here. Still, with the flip of a switch, I could turn on my central heating and a cold shower would do me no harm — for crying out loud. The United States is the second-largest consumer of electricity in the world, after China, with more than 3.9 trillion kilowatts per hour used each year. The Congo, by contrast, is the eleventh largest country in the world and yet just 9% of its 85 million people have access to electricity. Even Kananga, the provincial capital of Kasai Central with about half a million people, only gets electricity on and off from about 11 a.m. until sundown. And estimates are that that fewer than 10% of the people in the ramshackle city still recovering from three years of violent conflict are connected to the national power company, SNEL. If you ask people in Kananga why the power hasn’t improved over the years, many will tell the 32-year dictator Mobutu Sese Seko and his successors, Kabila father and son, like to keep a grip on power by dictating when it’s lights on — and lights out. |

Solar units for sale in Kamponde, Congo

|

We stayed with Jim, who comes from a revered political family in the Kasai and was recently elected to the state assembly. His father, Barthélemy Mukenge, was the first governor in Kasai after independence; he died last year at 93 years old and the city erected a statue in his honor. And yet, Jim and his wife Bernadette — both of whom went to college in the States — rent an old colonial house in Kananga with no running water and spotty electricity.

If they chose to use the national power company, it would cost them $80 to $100 a month. That, in a country where the GDP per capita was only $495 last year and most make fewer than $100 a month. Jim instead pays $50 a month to be hooked up to a neighborhood generator, where some 25 houses share the electricity and get more hours out of it than SNEL.

If they chose to use the national power company, it would cost them $80 to $100 a month. That, in a country where the GDP per capita was only $495 last year and most make fewer than $100 a month. Jim instead pays $50 a month to be hooked up to a neighborhood generator, where some 25 houses share the electricity and get more hours out of it than SNEL.

|

Jim and Bernadette are among the educated, political class. She has a great job with the massive United Nations’ operations in Kananga. They can afford a small village to help them run their household, fetching petrol for their generators, cooking over coal fires, gathering water from the local wells for their laundry, cooking and bathing.

Still, it’s just an endless day of gathering, carrying, prepping and stoking. It’s so frustrating. The DRC is endowed with mountains of precious minerals, yet much of it is mined using child labor and little of the proceeds trickle down to the help the people. The mighty Congo River has the potential to install up to 100,000 MW of hydropower capacity, enough to help electrify much of the African continent, according to USAID. |

Best. Sauce. Ever.

We had it over some spaghetti on our last night in Kananga. |

Yet some 60 years of dictatorship and corruption since independence in 1960 has left the country, formerly known as the Belgian Congo and Zaire, completely broken. In a country the size of the United States east of the Mississippi, there are fewer than 1,000 miles of paved roads — compared with more than 4 million miles of paved roads here at home.

The mere 60 miles between the city of Kananga and my Peace Corps village, Kamponde, is not only unpaved, but ravaged by foot-deep ruts and yard-wide sand pits or yawning puddles. It took us four hours to get about two-thirds of the way there in a 4x4 — we had to give up due to monsoon rains and stay in a guest house in Tshimbulu — and six hours driving straight back at the end of the week.

Jim actually helped build a hydroelectric dam just outside of Kananga, one that began giving 24-hour electricity to the Good Shepherd Hospital in Tshikaji back in 1985. Today, the plant still powers what is now the Christian Medical Institute of Kasai (IMCK), which has 140-bed teaching hospital, a lab tech school and college-level nursing program, as well as specialized programs in dentistry, surgery, opthalmology, maternity and pediatrics.

The mere 60 miles between the city of Kananga and my Peace Corps village, Kamponde, is not only unpaved, but ravaged by foot-deep ruts and yard-wide sand pits or yawning puddles. It took us four hours to get about two-thirds of the way there in a 4x4 — we had to give up due to monsoon rains and stay in a guest house in Tshimbulu — and six hours driving straight back at the end of the week.

Jim actually helped build a hydroelectric dam just outside of Kananga, one that began giving 24-hour electricity to the Good Shepherd Hospital in Tshikaji back in 1985. Today, the plant still powers what is now the Christian Medical Institute of Kasai (IMCK), which has 140-bed teaching hospital, a lab tech school and college-level nursing program, as well as specialized programs in dentistry, surgery, opthalmology, maternity and pediatrics.

|

We stopped by on our way back from Kamponde and Jim found that his old colleagues who worked with him way back when he was the operations manager were still there, working the turbines and protecting the plant during the recent Kasai uprising. It was a beauty to behold.

Still, why can’t this be emulated throughout a country blessed with vast rivers and endless ingenuity? Most will tell you: government corruption, decades of conflict— and the exhaustion that comes from always being let down. The newly elected President Félix Tshisekedi has his work cut out for him. Beth Duff-Brown is the editor of Stanford Health Policy and It Took a Village: A Congo Journey This is a special publication for American Energy Society. Please visit Beth's blog. |

The turbines inside the Tshikaji Hydroelectric Dam

|