Tensions are rising in the Persian Gulf, following a string of attacks on oil tankers over the last month. The United States just announced that it is sending 1,000 additional troops to the region to address threats to U.S. personnel and interests. Nonetheless, oil markets seem unperturbed, reacting more to economic news than fears of disruption and shortage.

|

The first four tanker attacks occurred on May 12, in the Gulf of Oman near the United Arab Emirates port of Fujairah. There were no injuries to the ships’ crews or spills of oil or other materials. An international investigation found that the attacks involved limpet mines attached to the ships’ hulls and that the attacks were designed to disable the ships, not destroy them. The investigation pointed to the involvement of a “state actor,” but did not mention Iran by name, although both Saudi and U.S. officials pointed to Iran as the culprit.

|

__________________________________________________________________

Oil markets have reacted to these events with a shrug and a yawn. ___________________________________________________________________ |

The second round of attacks on June 13 was an escalation. A Japanese tanker carrying methanol and a Norwegian tanker carrying naphtha were attacked in international waters in the Gulf of Oman. The Norwegian tanker caught fire and both ships’ crews sent distress signals and were rescued. U.S. officials have been much more strident in blaming Iran this time, sharing video allegedly showing an Iranian patrol boat retrieving an unexploded mine from one of the damaged ships. (Iran is denying its involvement, but evidence certainly points in that direction, and Iran has every reason for carrying out the attacks.)

Oil markets have reacted to these events with a shrug and a yawn.

After attacks on six tankers in just over a month, one might expect sky-high oil prices and market panic. Yet oil markets have reacted to these events with a shrug and a yawn. Prices for the main benchmark crudes rose a percent or two on Friday after the most recent attacks, then fell again in the following days. Overall, crude oil prices are down more than $10 in the last two months, during the time when the attacks have taken place.

SUPPLY CONCERN VS. ECONOMIC FEAR

Oil markets have reacted to these events with a shrug and a yawn.

After attacks on six tankers in just over a month, one might expect sky-high oil prices and market panic. Yet oil markets have reacted to these events with a shrug and a yawn. Prices for the main benchmark crudes rose a percent or two on Friday after the most recent attacks, then fell again in the following days. Overall, crude oil prices are down more than $10 in the last two months, during the time when the attacks have taken place.

SUPPLY CONCERN VS. ECONOMIC FEAR

|

Why has the market reaction been so muted? For the past several months, oil prices have been experiencing a tug-of-war between opposing sentiments—geopolitical concerns and economic concerns. On the geopolitical side, instability and falling oil production in Venezuela and Libya have put upward pressure on oil prices, along with the full implementation of sanctions on Iranian oil production. At the same time, economic concerns are putting downward pressure on oil prices. Economic growth in China is slowing and the world is concerned that the current U.S. trade war with China will expand and drag down the global economy.

|

At this time, even with the tanker attacks, concerns about lagging economic growth are winning and oil prices are at their lowest level since early January.

Markets Believe That The Strait of Hormuz Will Stay Open

Markets Believe That The Strait of Hormuz Will Stay Open

Another important element in the muted response to the tanker attacks is that they could have been much worse. None of the ships that were attacked carried crude oil. Five of the six ships were quite small. The sixth ship was a Saudi-flagged supertanker, but it was empty, on its way to pick up crude oil at the Ras Tanura terminal in the Kingdom. The attacks seem to have been designed to send a message without actually disrupting markets.

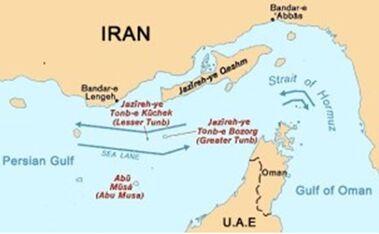

Rising tensions in the Gulf always bring fears of the granddaddy of oil supply disruptions—closure of the Strait of Hormuz. Approximately 20 percent of the world’s oil supply flows through this narrow passage, with Iran on one side and Oman and the UAE on the other.

Clearly, closure of the strait for any length of time would cause skyrocketing oil prices and genuine shortages of crude oil. Iran periodically threatens to close the strait when it is under duress, and it made such a threat in April in response to the United States working to end Iranian oil exports. However, an attempt to shut down the strait would be suicidal for Iran. The U.S. Fifth Fleet, based in Bahrain, would immediately react, making it very hard for Iran to block naval traffic. Additionally, closure of the strait would unite the world’s oil importers against Iran. At a time when Iran is struggling under U.S. sanctions, it can ill afford to antagonize countries like China that are inclined to side with it against the sanctions and to find work-arounds.

However, one market is responding strongly to the tanker attacks—the insurance market. Insurance premiums for tanker ships moving crude oil in the Middle East have skyrocketed and are now up to 20 times their level before the attacks. Some underwriters are reluctant to provide insurance at all. Raising shipping and insurance rates and striking fear into those navigating in the Gulf may be the most important lingering impacts of the attacks.

Iran does not need to close the Strait of Hormuz to make its point. Iran is also suspected of involvement in drone attacks on Saudi Arabia’s East-West Pipeline, which allows oil exports to bypass the Strait of Hormuz. As my colleague Suzanne Maloney has described in detail, Iran is backed against the wall and looking for a pathway out of the current standoff and U.S. sanctions. Acts that disrupt oil trade are intended to raise pressure on the United States and the world to return to the negotiating table and end the sanctions. Iran can achieve that goal with smaller scale acts of sabotage that are plausibly deniable, hard to deter, and less likely to elicit an overwhelming military response.

Permission to republish the original article granted by The Brookings Institute.

Rising tensions in the Gulf always bring fears of the granddaddy of oil supply disruptions—closure of the Strait of Hormuz. Approximately 20 percent of the world’s oil supply flows through this narrow passage, with Iran on one side and Oman and the UAE on the other.

Clearly, closure of the strait for any length of time would cause skyrocketing oil prices and genuine shortages of crude oil. Iran periodically threatens to close the strait when it is under duress, and it made such a threat in April in response to the United States working to end Iranian oil exports. However, an attempt to shut down the strait would be suicidal for Iran. The U.S. Fifth Fleet, based in Bahrain, would immediately react, making it very hard for Iran to block naval traffic. Additionally, closure of the strait would unite the world’s oil importers against Iran. At a time when Iran is struggling under U.S. sanctions, it can ill afford to antagonize countries like China that are inclined to side with it against the sanctions and to find work-arounds.

However, one market is responding strongly to the tanker attacks—the insurance market. Insurance premiums for tanker ships moving crude oil in the Middle East have skyrocketed and are now up to 20 times their level before the attacks. Some underwriters are reluctant to provide insurance at all. Raising shipping and insurance rates and striking fear into those navigating in the Gulf may be the most important lingering impacts of the attacks.

Iran does not need to close the Strait of Hormuz to make its point. Iran is also suspected of involvement in drone attacks on Saudi Arabia’s East-West Pipeline, which allows oil exports to bypass the Strait of Hormuz. As my colleague Suzanne Maloney has described in detail, Iran is backed against the wall and looking for a pathway out of the current standoff and U.S. sanctions. Acts that disrupt oil trade are intended to raise pressure on the United States and the world to return to the negotiating table and end the sanctions. Iran can achieve that goal with smaller scale acts of sabotage that are plausibly deniable, hard to deter, and less likely to elicit an overwhelming military response.

Permission to republish the original article granted by The Brookings Institute.